10-Year Yield: Why the Hot Inflation Bounce Didn’t Last

US10Y…

-0.32%

Add to/Remove from Watchlist

Add to Watchlist

Add Position

Position added successfully to:

Please name your holdings portfolio

Type:

BUY

SELL

Date:

Amount:

Price

Point Value:

Leverage:

1:1

1:10

1:25

1:50

1:100

1:200

1:400

1:500

1:1000

Commission:

Create New Watchlist

Create

Create a new holdings portfolio

Add

Create

+ Add another position

Close

Yesterday I outlined the case that several ‘fair-value’ models suggest the current US 10-year Treasury yield appears high relative to the fundamentals.

As a quick follow-up, what does a simple empirical review of historical suggest vis-à-vis the 10-year rate and the latest offending inflation data point that triggered a sharp rise in the benchmark yield on Tuesday?

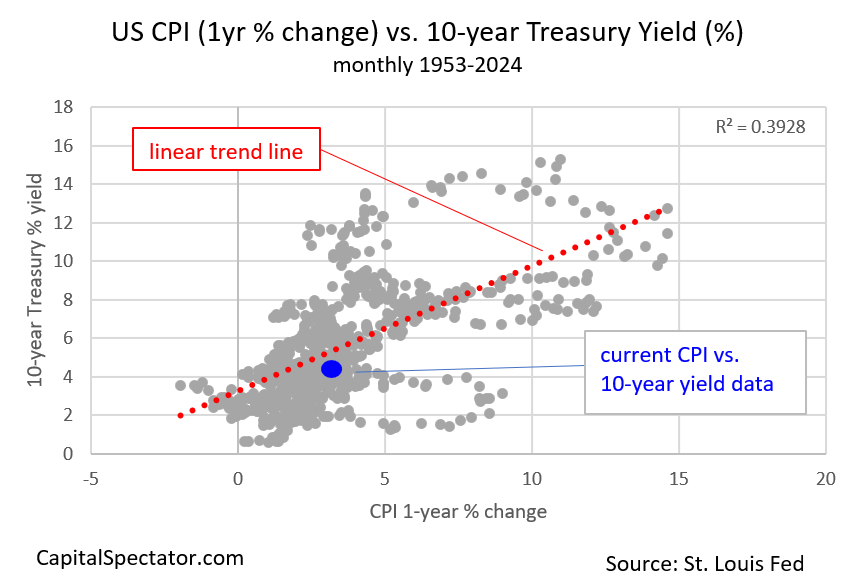

For some perspective, consider monthly data for the 1-year percentage change in the headline consumer price index (CPI) vs. the current 10-year yield through time since the mid-1950s through January 2024.

As the chart below suggests, there’s a moderate, albeit variable link with an R-squared of roughly 0.4.

US CPI vs 10-Year Treasury Yield

US CPI vs 10-Year Treasury Yield

The main takeaway: inflation and Treasury yields move together to a degree, but they’re hardly joined at the hip in the short term.

At times the relationship breaks down and one or the other can veer sharply away from the other. In other words, almost anything’s possible in the short term.

A key issue for thinking about this dance is causality, namely: Which series is driving the other? For the most part, it’s reasonable to assume that inflation influences the 10-year, although at times the causality can flow the other way.

The current relationship (blue dot in the chart above) suggests that the 10-year yield is a bit below the level that the historical linear relationship suggests is “normal”.

By contrast, the average modeling outlined yesterday points to a 10-year yield that’s well above fair value.

Which approach is accurate? Impossible to say for a simple reason: No one knows which “model” Mr. Market uses to price Treasury yields.

But there’s at least one common theme in both model exercises: the odds appear relatively low that the 10-year yield will spike higher from current levels (4.27% as of Feb. 14).

That’s hardly a bulletproof forecast, but it’s a reasonable baseline. To argue that a much different future awaits for the 10-year yield – sharply higher or lower levels vs. the current rate – requires a hefty dose of forecasting results that point to inflation’s path ahead.

That can be a useful exercise as well, but keep in mind that forecasting much beyond the immediate future for interest rates and inflation ventures into a far more speculative realm vs. the analysis presented above and yesterday.